🏏 Will bat continue to dominate ball at the Women’s T20 World Cup?

My Week in Sport(s): cricket in the UAE, Mbappé at Madrid and an All Black starlet

Welcome to My Week in Sport(s) — a regular newsletter from Plot the Ball.

In this edition:

🏏 Balancing risk and reward in short-form cricket

⚽️ How Kylian Mbappé’s game has changed in La Liga

🏉 Wallace Sititi’s neat footwork for New Zealand

🏏 Will bat continue to dominate ball at the Women’s T20 World Cup?

The introduction of a new set of rules — or of a new format altogether — can be an excellent opportunity for a sport to take stock of what it really knows about itself.

Twenty20 cricket is a good example of this. The shortest format of the sport has now been around for more than two decades — and its arrival has really focused the thinking of analysts on the question that underpins basically every sporting contest.

What is the optimal amount of risk that an athlete or team should take in order to maximise its expected reward on the scoreboard?

In every format of cricket1, two constraints frame this question: the number of remaining deliveries available to the batter to accumulate runs, and the number of times a player from their team can be dismissed before their innings is deemed complete.

T20 forced the issue in the minds of observers by radically decreasing the former from the sport’s traditional formats, while keeping the latter constant.

Even though it’s been played since 2003, players and coaches probably still haven’t recalibrated aggressively enough to these altered constraints; teams rarely make full use of their available resources.

The women’s game, in particular, is in an interesting place right now.

The 2024 Women’s T20 World Cup got underway in the United Arab Emirates earlier this week. It’s the ninth time the trophy has been contested since the inaugural edition in 2009.

But the frequency of international T20 matches has increased significantly over those 15 years: around 80% of all of the T20Is for which ESPNCricinfo has available records have been played since 2018.

It’s fair to class this period of six years as the format’s ‘modern era’, I think.

And when you analyse how teams have approached balancing risk and reward over this period, the results aren’t necessarily what you’d expect.

Six teams qualified automatically for this edition of the World Cup: Australia, the defending champions, as well as England, India, New Zealand, South Africa and the West Indies.

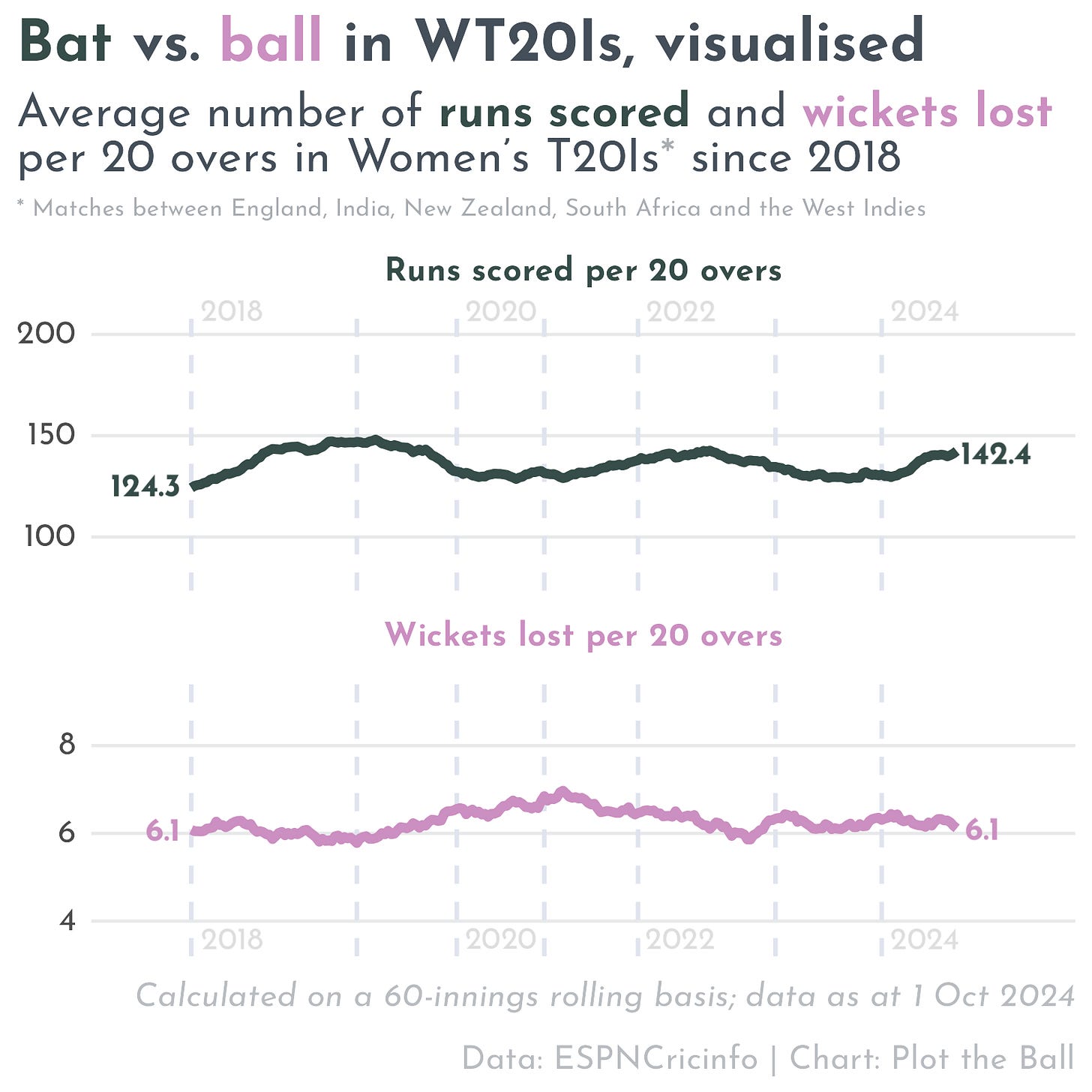

In games they’ve played against one another since 2018, the rate at which runs have been scored has been on the rise. Overall — on a 60-innings rolling basis — it jumped about 18% between the end of 2017 and the beginning of this year’s World Cup.

Batters have been able to push scoring rates higher without wasting additional resources, though: these teams were losing approximately 6.5 wickets per 20 overs at the start of 2018, and are only losing about 6.2 now.

But one of these six teams is not like the others.

Australia are not only the current world champions in the format. They have won six of the eight T20 World Cups to date — and, in matches against this top tier of teams since 2018, they have also recorded around 6 WT20I wins for every loss they’ve suffered2.

Including such a dominant outfit in our analysis — even if there may recently have been signs of a slip — might obscure broader trends in the game.

Narrowing our focus doesn’t materially change the key finding, though. When these other five top T20 teams play each other, they are taking on more risk to score faster — but without seeming to incur any additional cost.

The rate of run-scoring in these fixtures is up by about 15% since the start of 2018; the average number of wickets lost per 20 overs has fluctuated a bit over this period, but has settled again at around 6.1 — the same as at the end of 2017.

Where does that leave us as this World Cup gets started?

Australia begin their campaign today against Sri Lanka — and this data does put their relatively poor recent performance with the ball in context.

If other top teams have been improving the efficiency of their run-scoring in general, then the higher rate at which Australia have recently tended to concede runs might have more to do with the quality of their opponents than a decline in their own skill levels.

That’s particularly interesting when you consider the wider context of the sport, too.

Franchise leagues have begun to proliferate in the women’s game as they have in the men’s — and are drawing players from around the globe to compete with and against one another.

Opportunities to learn from the best are more frequent than ever — as England batter Alice Capsey recently pointed out in an interview with ESPNCricinfo:

At the age of only 20, Capsey has already played a remarkable amount of cricket all over the world — and she’s had opportunities to grow that similarly talented cricketers coming through the same system a decade earlier simply wouldn’t have had.

And it seems like these developments have had more of a positive impact on batters like her than on the bowlers who are trying to stop them scoring.

Things have been a bit slower than expected in the early matches of this World Cup, though. In the two games so far between teams in this top tier of six, batters have scored at a rate of around 130 runs per 20 overs — and forfeited 5.2 wickets on average.

Both figures are lower than the pre-tournament figures we calculated above.

This relative conservatism might be a reflection of the considerable uncertainty around how conditions in the UAE are going to play; the tournament was relocated from Bangladesh at short notice3.

As Raf Nicholson of The Guardian pointed out earlier this week:

The countries that continue to be aggressive even in the face of this uncertainty could be rewarded over the coming weeks, then.

In cricket — as in many other sports — teams are still leaving value on the table when weighing up how much risk is really worth taking.

⚽️ Run the Numbers

Let’s leave to one side for now the question of what the addition of Kylian Mbappé has meant for the strength of Real Madrid as a team4. What has the move to Real Madrid meant for the game of Kylian Mbappé?

To start with, there’s been a notable shift in his role in his team’s ball progression: he is stationed further up the field, and has less responsibility for moving the ball towards goal.

How do we know this?

It’s clear in his tally of progressive actions: through seven La Liga matches, per FBref, he is averaging around 0.5 fewer progressive passes per 90 minutes compared to his final season in Ligue 1 — and 1.8 more progressive receptions.

It’s also clear in the overall number and spread of his touches: despite falling around 13% in total across the field, they are up 40% — from 8.6 per 90 to 12.1 — in the attacking penalty area.

He’s spending more time in the most dangerous areas of the field, then, and this also shows up in his shot numbers.

He’s taking around 0.7 more shots per 90 — and they’re coming from 2.8 yards closer to the goal than last year, on average. The net impact of this is that he’s actually producing more non-penalty expected goals on a per-minute basis than last year5.

This increase has been more than offset by a decrease in the quality of the scoring chances he’s assisted, though: his non-penalty xG assisted is down from above 0.2 per 90 minutes last season to below 0.1 in Madrid colours.

In summary: the integration of the signing of the summer is still a work in progress.

🏉 Watch the Games

2024 so far has been a relative struggle for the All Blacks, New Zealand’s typically dominant men’s national rugby team.

For only the third time since the expansion of the Rugby Championship to four nations in 2012, they failed to win the title outright6 — and this year was the first time they’d finished outside the top spot in a full-length7 edition of the tournament.

One bright spot, though, has been the emergence of a potential star: Wallace Sititi.

The 22-year-old — making only his third test start in the back row — had a crucial hand in his team’s first try of their game against Australia in Wellington last Saturday.

Receiving a pass in midfield shortly after New Zealand had forced a turnover, Sititi steps hard off his right foot to stop their drift across the field — and force the defender opposite him, Matt Faessler, to sit down onto his heels.

He only takes two more paces before switching direction again, though. Following a second sidestep off his left, he shimmies into a gap on his marker’s outside shoulder and attracts the attention of Hunter Paisami, Australia’s next defender along.

By briefly freezing that second man with a dummied pass to his outside, Sititi is able to sneak through the defensive line.

Then — by releasing the ball just before Faessler brings him to ground — the forward can send his support runner into the space that Paisami has vacated to pick off the remaining Australian cover.

Within 10 seconds of Sititi touching the ball, New Zealand are over the try line.

You can watch a clip of this sequence here.

The next edition of My Week in Sport(s) will be published on Saturday October 12th.

I’ve written about the England men’s test team’s novel — but not necessarily rational — approach to this question a couple of times over the last couple of years.

England have the next-best ratio in the format over this period, at around 3 times the number of wins as losses.

I will say that it’s already made for some interesting pass maps.

We can also leave to one side — based on his track record — a brief shooting slump that has seen him record 2.6 fewer non-penalty goals than expected based on his shot locations.

An average points difference per game of +6.2 also compares very poorly to their historical performance levels; it’s comfortably their lowest mark in a full-length Rugby Championship campaign.

In years that the Rugby World Cup takes place, an abridged tournament is held.