⚾️ Can Yoshinobu Yamamoto defy gravity in Major League Baseball?

My Week in Sport(s): baseball's latest Japanese star, 'Bazball' and Caitlin Clark

Welcome to My Week in Sport(s) — a new regular newsletter from Plot the Ball.

In this edition:

⚾️ Yoshinobu Yamamoto’s transition from NPB

🏏 The extraordinary batting of the England men’s test team

🏀 Caitlin Clark’s unprecedented scoring

⚾️ Can Yoshinobu Yamamoto defy gravity in Major League Baseball?

It’s gratifying to be reading about a familiar topic and discover a completely new way of talking about a commonly formulated problem.

Football analyst Ian Graham — formerly of Liverpool — gave me such a moment when he was interviewed by Rory Smith of the New York Times last year.

Explaining one of the reasons why he thinks the sport in which he now makes his living is more complex to analyse than the scientific discipline in which he got his PhD, Graham said:

Germany doubtless wasn’t a randomly chosen example, either.

The country’s top men’s football league is often cited as the prime example of the underlying issue that Graham is alluding to: the difficulty of projecting athletes’ future performance levels in a new context, based on their historic performances in a different one.

This issue doesn’t crop up as often in discussion of any the four major men’s leagues of North America as it does in European football.

Each league is pretty clearly positioned at the top of the pyramid of its respective sport — and you can be much more confident that almost all of the most talented athletes are already playing there.

But every once in a while it becomes a topic of major interest.

So it was over Major League Baseball’s winter break, when the Los Angeles Dodgers agreed a huge contract with arguably1 the best Japanese pitcher not named Shohei Ohtani — shortly after signing Ohtani himself away from their crosstown rivals, the Angels.

Giving Yoshinobu Yamamoto a 12-year, $325mn deal is an indication that the Dodgers are pretty confident he will perform well after moving over to North America from Nippon Professional Baseball, where he was one of the Japanese domestic league’s stars.

How will they have arrived at this judgement, though?

As Ian Graham alluded to in that interview, adjusting player statistics for the context of the league in which they played can be really complicated.

Let’s see if we can simplify things a bit and get a rough idea of his level.

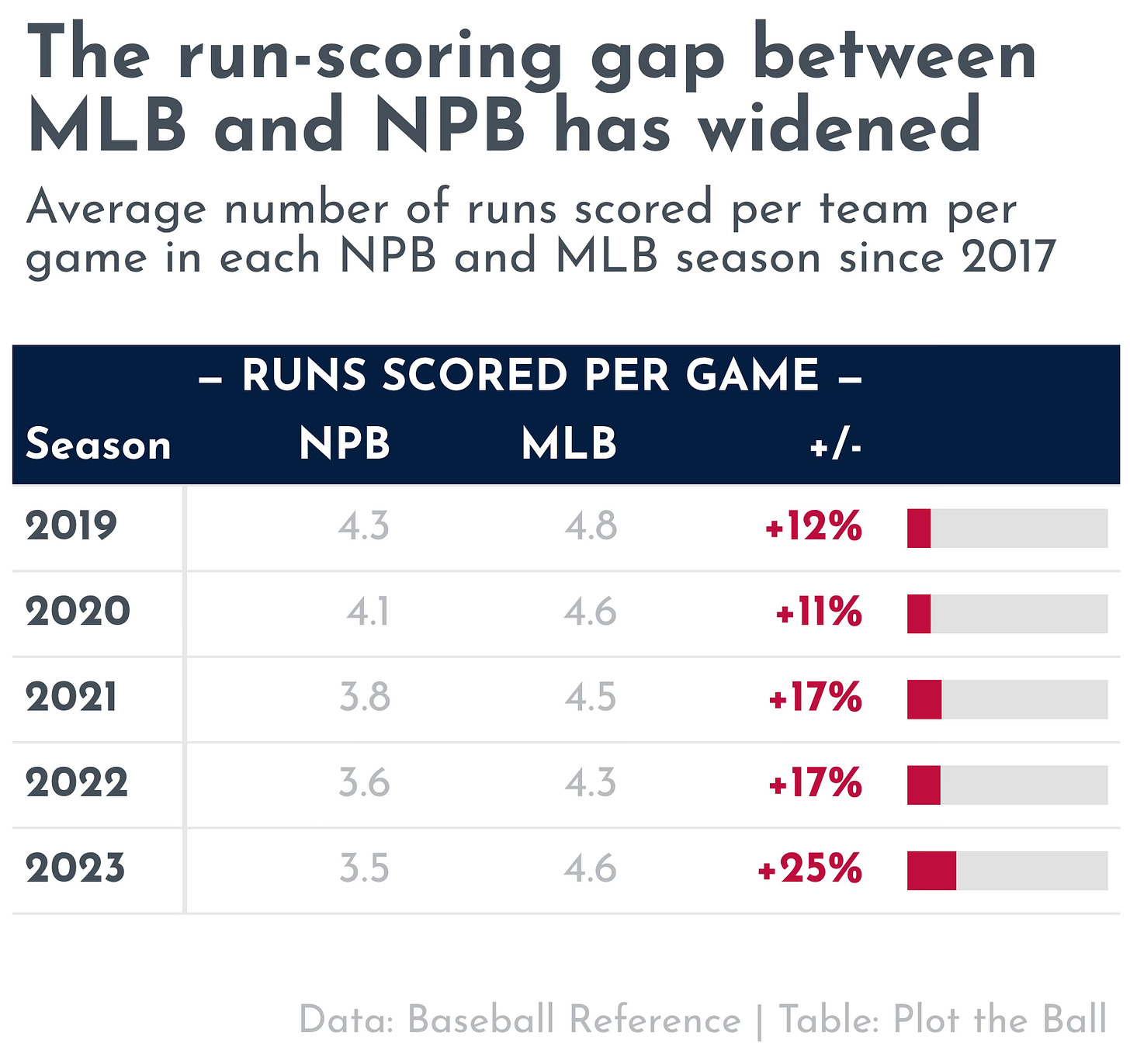

One of the easiest things to compare between leagues is the overall rate of scoring — and we can see that, over the last five seasons, there have been considerably fewer runs scored in NPB games than in MLB games.

In 2023, the average NPB team scored 3.5 runs per game — while the average MLB team scored 4.6.

This is the context in which we have to place Yamamoto’s top-line numbers, to start with.

His career Earned Run Average in NPB of 1.82 per nine innings sounds impossibly good if you’re used to dealing in MLB figures — but add on another third of a run, as the table above might suggest you should, and it becomes merely league-leading.

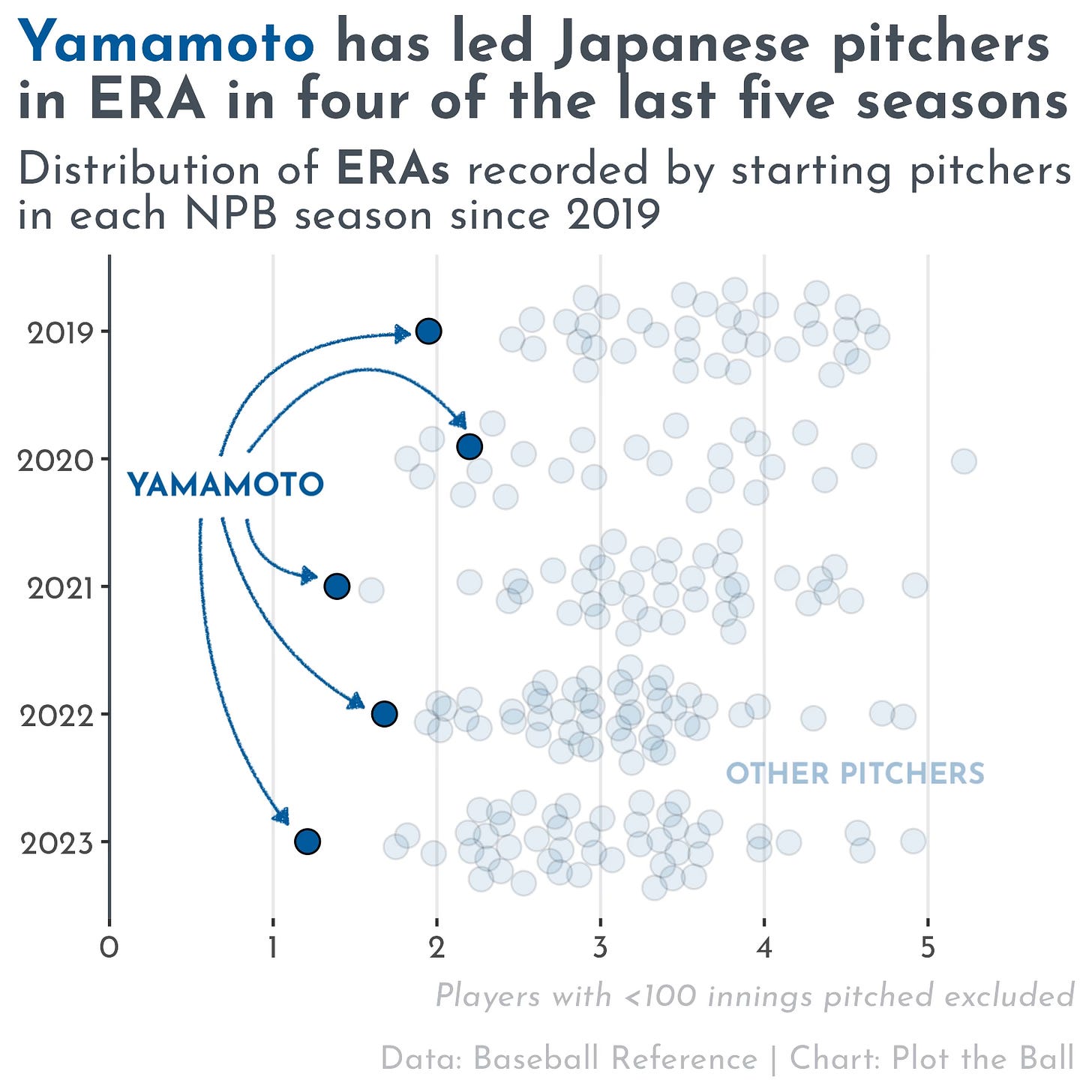

Even accounting for the lower rate of overall scoring, though, it’s worth emphasising: Yamamoto has been consistently the best pitcher in Japan over his career to date.

Since becoming a full-time starter, he has led NPB in ERA in four out of five seasons.

No Japanese pitcher — not even Ohtani2 — has come over to the Majors with such an accomplished track record in their domestic competition.

Domestic records don’t count for everything, though. Facing more talented hitters taking more progressive approaches3 in MLB, some pitchers’ skills and tendencies simply match up better with their new opponents than others’.

To illustrate: a number of pitchers moved over from NPB to MLB in the late 2000s.

The most vaunted was Daisuke Matsuzaka, whose rights the Boston Red Sox paid an enormous fee for when he became available.

But Matsuzaka — despite excelling in NPB — was merely a league-average pitcher in the Majors over his career, while other less-heralded pitchers from the same era did considerably better4.

The difference in the 2020s is that we no longer have to rely solely on traditional metrics and analysis methods in order to project Japanese pitchers’ effectiveness5.

Many North American ballparks are now equipped with advanced tracking technology which measures in minute detail how the baseball travels through the air after leaving a pitcher’s hand.

The technology was also available during last year’s World Baseball Classic — and Yamamoto’s appearances in the tournament for Japan meant that teams looking to sign him had access to some detailed evidence on his ‘stuff’, to go with the extensive track record.

The verdict, per MLB.com’s David Adler: “his stuff looks good. Really good.”

Take all of this together, and you can see why the Dodgers rate Yamamoto’s chances of success. Public analysts also agree: FanGraphs is projecting him to be a top-10 pitcher in his first year in the Majors.

We just won’t know for certain until we see Yamamoto do it, though. When you take such a big jump between competitions, you can never be sure just how quickly you’ll hit the ground on the other side.

🏏 Run the Numbers

England’s approach to batting in men’s test cricket under head coach Brendon McCullum has so far been as effective6 as it is novel.

You need extraordinary evidence to conclude that the basic truths of a given sport don’t apply to a specific team, though — and some analysis of this England team is starting to stretch the available data.

It’s useful as a guideline to consider that, over the last couple of years of men’s tests, batters have been dismissed on roughly one in every 10 of the ‘false shots’ they play7.

After England defeated India last week in Hyderabad, CricViz’s Head of Insight wrote in a piece for the Hindustan Times:

He goes on to say that “[w]ith defensive fields becoming an orthodox response to Bazball’s unorthodoxy… England’s false shots [are] far less likely to lead to a wicket”.

This sounds plausible — but it isn’t really true, as far as we can tell from looking at the public record.

After the first test of the current series, Kartikeya Date of A Cricketing View helpfully summarised the rate at which test teams in the McCullum era have been dismissed relative to the number of false shots they play.

England are among the teams with the highest number of false shots committed per dismissal over this period — but they certainly aren’t an anomaly, and there’s no evidence that the rough guideline of ‘10 false shots per dismissal’ shouldn’t apply to them like it does to every other nation.

The takeaway therefore can’t be that ‘England aren’t bound by the same rules as other batting teams’. So how should we think about their success?

S Rajesh of ESPNCricinfo wrote the definitive analysis of England’s batting approach after last summer’s Ashes — and published a further piece after last week’s match. As he puts it:

England aren’t operating outside of the traditional risk-reward trade-off; they have found a more efficient strategy for their batting talent by consciously embracing it.

🏀 Watch the Games

Iowa’s Caitlin Clark — closing in on multiple NCAA scoring records — is almost in unprecedented territory for a college basketball player.

And a lot of her offensive success is down to the accuracy of her shooting from way beyond the three-point line — which holds up in comparison to almost anyone else in the sport.

Possessing that sort of range forces defenders to pay close attention to you in unfamiliar parts of the court — and Clark used that to her advantage late in the third quarter against Northwestern on Wednesday.

After initiating a pick and roll above the three-point line with 10 seconds remaining, she is immediately chased towards the left sideline by a pair of defenders.

Forced to turn back towards half-court, as she picks up her dribble she will know that somewhere behind the double coverage is a free teammate. But Clark goes mismatch hunting instead — and throws a bullet over four defenders to a teammate with a size advantage underneath the basket.

No matter how comfortable you are shooting from deep, there’s rarely a better shot to create for your team than a gimme lay-up.

You can watch a clip of this sequence here.

The next edition of My Week in Sport(s) will be published on Saturday February 10th.

I say ‘arguably’ because of the existence of Roki Sasaki — but that’s a topic for another newsletter.

Of the pitchers to come over from NPB this century and pitch as many MLB innings as Ohtani has so far, it’s actually Yu Darvish who has the best domestic record: a 1.99 career ERA.

From a 2017 piece on the adoption of sabermetric-driven approaches to the game in Japan: “many NPB teams still make major mistakes that most MLB teams have moved past, such as…embracing excessive small ball; batting powerless slap-hitters second…and building around pitching and defense, regardless of circumstance.”

Matsuzaka’s career ERA+ (a metric which rebases ERA, with 100 as league average) was 99; Hiroki Kuroda — whose MLB career began a year later, after recording a considerably higher career ERA than Matsuzaka in Japan — had an ERA+ of 115 in the Majors.

A current MLB general manager explained it thus in an interview with The Athletic: “pitch-grade evaluation…is so different than when we were going through the same process with Dice-K [Matsuzaka]…A lot of the stuff that’s under the hood and available today just wasn’t available then. So it is a different ballgame.”

They have scored 37.4 and 40.6 runs per dismissal respectively during their last two home summers (2022 and 2023), having recorded the following batting averages as a team in the five preceding summers: 27.2 (2021), 39.7 (2020), 26.1 (2019), 29.6 (2018) and 33.6 (2017).

This is a simplification of the record presented by cricketingview on X here.