⛳ Is Rory McIlroy the second-best men's golfer of the 21st century?

Trophy hunting

Welcome to the eighth edition of Plot the Ball — a newsletter where I offer data-driven answers to interesting questions I have about the world of sport.

This month — after watching Rory McIlroy become the first-ever three-time FedEx Cup Champion a few weeks ago — I’ve been thinking about conventional assessments of the Northern Irish golfer’s career to date, and wondering whether there’s a way to judge his achievements more objectively.

Is Rory McIlroy the second-best men's golfer of the 21st century?

Even before his third FedEx Cup win at East Lake last month, it was clear that Rory McIlroy had no real insecurities about his own golfing ability.

Nonetheless, given the high level of play he’s now sustained for many years, some of the commentary around his game can be a bit perplexing.

Bluntly, a lot of the criticism he receives is often what the Indian cricket writer Kartikeya Date has ingeniously termed ‘psycho-babble’: nebulous discussions of an athlete’s apparent mindset and questionable interpretations of their body language, rather than a focus on the physical and technical specifics of the actual sporting contest at hand.

(Or, as Date describes it, “physical labour involving the mastery of extremely complex skills”.)

What if we tried to have a more objectively-grounded conversation about McIlroy’s career to date?

Mercifully, the website Data Golf — expertly maintained by brothers Matt and Will Courchene — allows us to do exactly that.

They have built their own world-rankings model based on the sport’s flagship analytical measure, Strokes Gained1 — a model2 which currently ranks McIlroy as the most skilled golfer in the world.

And, if we look at the Strokes Gained data collected by Data Golf over the last few decades, only Tiger Woods has been better than Rory in recent history.

It’s worth emphasising just how far ahead of the field Tiger is by this metric.

Over his career, Woods has played 2.8 strokes better per round than the average PGA Tour professional — with McIlroy 0.9 strokes behind him at +1.9 per round.

For context, there are a further 44 players above +1.0 strokes gained on average over this period — or, to put it another way, 44 players closer to McIlroy than McIlroy is to Tiger.

(Not far behind Rory — at +1.87 strokes gained per round to his +1.90 — is Jon Rahm, but the Spaniard has sustained this level over a much smaller sample of rounds played.)

That’s all well and good, you might say — but McIlroy hasn’t always been able to step up and perform when it ‘matters’.

A swift response to this is that — again, according to Data Golf — McIlroy’s performance in majors by strokes gained has actually been stronger than you would expect given his level of play in non-major events.

A longer one, however, would emphasise that — because of the inherent randomness of the sport — the relationship between execution and outcome isn’t always a simple one in golf.

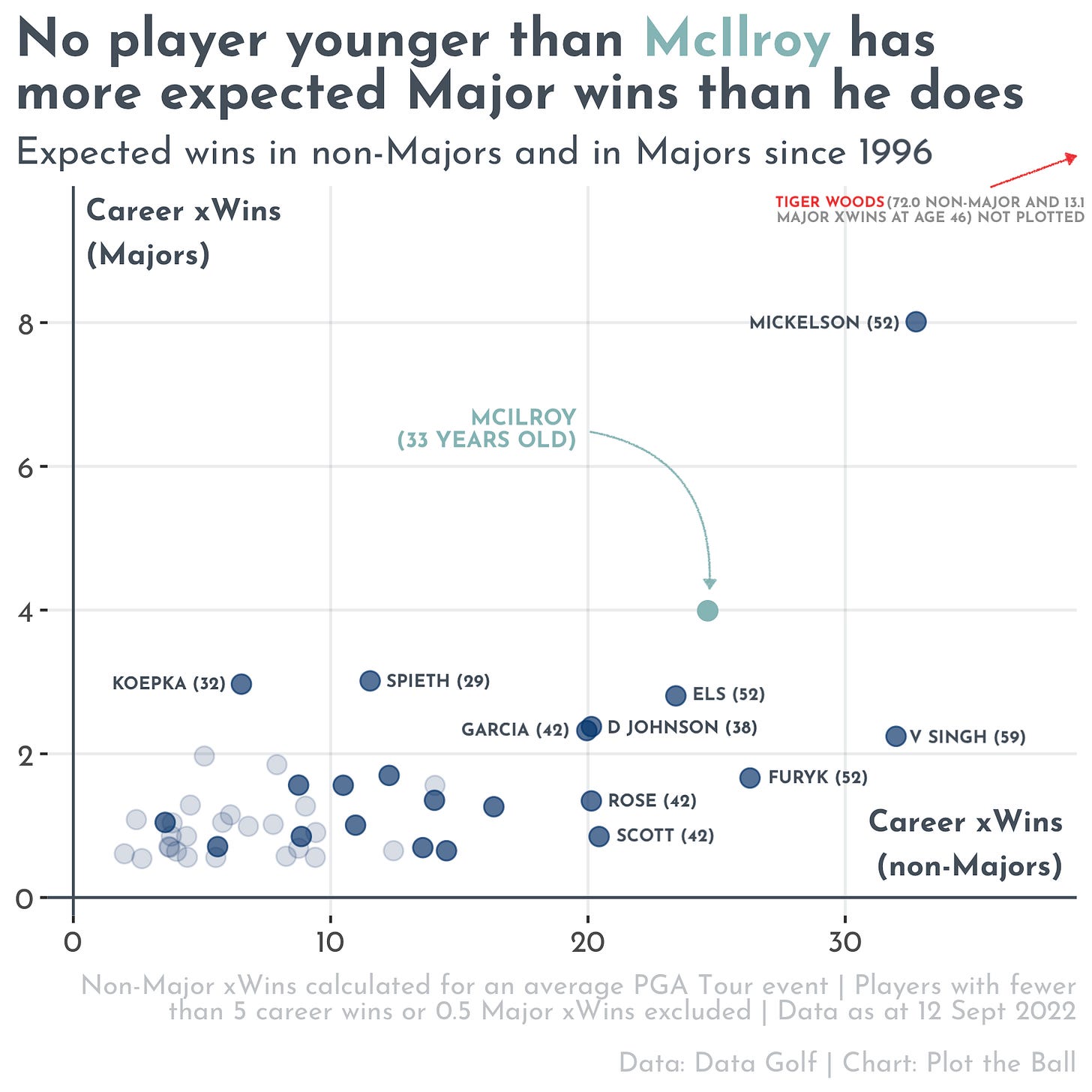

To try and deal with this issue, the Courchene brothers have also come up with an ‘expected wins’ model:

Expected wins measure the likelihood of a given strokes-gained performance resulting in a win. For example, averaging 3 strokes-gained per round (over the golfers who played all rounds in the tournament) at a full-field PGA Tour event will result in a win about 55% of the time. Why would this be good enough to win some events, but not others? Sometimes another player may also happen to have a great week and gain more than 3 strokes per round, while other weeks this doesn't happen. The intuition behind the expected wins calculation is simple. For example, to estimate expected wins for a raw strokes-gained performance of +3 strokes per round, you could just calculate the fraction of +3 strokes-gained performances that historically have resulted in wins.

Since 1996 — the season in which Tiger turned professional — only the performances of Phil Mickelson and Woods himself have accumulated more expected wins in majors than Rory’s3.

No one in their right mind would argue that McIlroy’s third turn as FedEx Cup Champion — a feat which no other golfer has accomplished — should vault him above Tiger4 in golf’s pantheon.

Based on these figures, however, Rory is as close to his level as anyone currently playing the sport.

And — irrespective of the noise that follows him around the world — it appears he knows it too.

Further reading

The Data Golf Blog on Rory (in 2017) and randomness in golf

Ewen Murray of The Guardian on Rory (in 2022) and the player’s thoughts on LIV Golf

Technical notes

You can find the code for this piece on GitHub here

There was one error I’d noticed in previous scatter plots I’d published which I was eager to correct this time around: including a solid reference line on axes with non-zero baselines. This was always going to be necessary for a plot like the first one above — where the vertical axis extends downward into negative territory — but the cleaner (and ultimately less misleading) look is one I’ll apply to all charts of this type going forward.

I also wanted to really work on my use of the annotation layer in this piece, in order to get the graphics to tell a clearer story by themselves. Hearing a second John Burn-Murdoch talk in the space of a few months this week — this time virtually at the StatsBomb Conference — focused my thinking on this even more; his chart on Liverpool’s evolution under Jurgen Klopp is one of my favourite examples of this being done well. I went through a very iterative process of adding and removing notes with the first scatter plot in particular, and am fairly happy with where I landed. That said, I’m going to make this more and more of a focus of the newsletter going forward as I still don’t think I’m harnessing the full narrative value of the data I’m using.

I went a bit more experimental with colours this month, using characteristic shirts worn by Tiger Woods and Rory McIlroy as inspiration. (I think Tiger’s classic red in particular really stands out well.)

Another edition of Plot the Ball, another shout-out for an amazing data resource. Literally none of this newsletter would have been possible without the work of Data Golf, and I can’t recommend it highly enough as a reference if you have even a passing interest in the sport.

Next month — with the 2022 NFL season already in full swing — I’ll be looking at the passing games of the league’s current crop of young franchise quarterbacks.

If you’re unfamiliar with the concept of Strokes Gained, this high-level breakdown on the PGA Tour’s website is definitely worth reading.

The FAQ section of the Data Golf website explains this model — and their adjustments to raw Strokes Gained figures — in more detail.

His major performances in 2022 alone — four top-10 finishes — earned him a total of 0.5 expected wins; this put him behind only Scottie Scheffler (1.02) and Cameron Smith (0.59) for the season.

We can’t be sure how many more FedEx Cup titles Woods — who has two — would have collected if the format had been instituted earlier than 2007, although we can hazard a rough guess. According to Data Golf’s expected wins database, he had the most non-major wins of any player in 7 of the 11 seasons between 1996 and 2006.