🏏 Charting the careers of the 'Big Four' of batting in men's test cricket

In tiers

Welcome to the fifth edition of Plot the Ball for 2023.

With the sheer quantity of great cricket on recently, I’ve been continuing to spend a lot of time watching and thinking about it — to the detriment of a few other sports1 . So — before the newsletter pivots in a different direction — here’s a final post for now on that topic.

Charting the careers of the 'Big Four' of batting in men's test cricket

It’s an odd feeling waking up and being somewhat surprised to see that Virat Kohli is scoring big runs in a test match.

The former Indian skipper will forever be grouped together with Joe Root, Steve Smith and Kane Williamson as the ‘Big Four’ of batting in men’s test cricket in the 2010s.

But — until his epic, eight-hour-long 186 over the weekend — the prolonged period of toil he has endured in recent years for little reward has been well documented2.

That’s not to say, however, that his place among the modern greats isn’t warranted.

To illustrate: there are eight (still-active3) test cricketers who debuted in 2010 or later who have scored more than 5,000 test runs at an average of better than 40 runs per dismissal.

And the so-called ‘Big Four’ possess records which are clearly the strongest of these eight players’ in aggregate. Kohli, Root, Smith and Williamson are the only four to average more than 45 runs per dismissal overall, as well as more than 40 away from home — in less familiar, and therefore more challenging, conditions.

Clearly, then, the ‘Big Four’ is a useful and merit-based heuristic.

But it’s worth acknowledging grouping the players together in such a way — and looking only at their career-level aggregates — can also obscure certain interesting stories about test batting over this period.

For starters, it’s arguable that — even among this small elite group — there’s separation between the top two and the rest.

Steve Smith has spent the entirety of his career — broken down into rolling 50-innings stretches — averaging more than 50 runs per dismissal, and most of it above 60; Williamson, meanwhile, has remained above a rolling average of 50 after a steady period of improvement at the start of his career.

Root, by contrast, has had a much more up and down career — starting strong, suffering through a prolonged spell at a rolling average of lower than 50 and more recently returning to form.

The chart above also captures the alarming downward trajectory of Kohli’s test career well; despite that 186 in his last match, over his most recent 50 innings he has averaged only 37 runs per dismissal.

There are, of course, other contextual factors4 in play here — not least the degree to which Indian pitches have become much more difficult to bat on in recent years.

Before the fourth and final test of the Border-Gavaskar Trophy series, Jarrod Kimber published an excellent, detailed piece on this phenomenon and how it has afflicted almost all of India’s top-order batters.

But the shapes of the careers of Kohli, Root, Smith and Williamson are a reminder that skill levels in elite sport are always relative — to the opportunities and threats presented by the skills and tendencies of other competitors, and to the challenges presented by the prevailing conditions — and that outcomes can vary considerably over time as a consequence5.

This variation in outcomes also means that — despite what the aggregate records say — we shouldn’t rule out the possibility that other players have, for periods, competed at equivalent (or higher) levels than some of the ‘Big Four’.

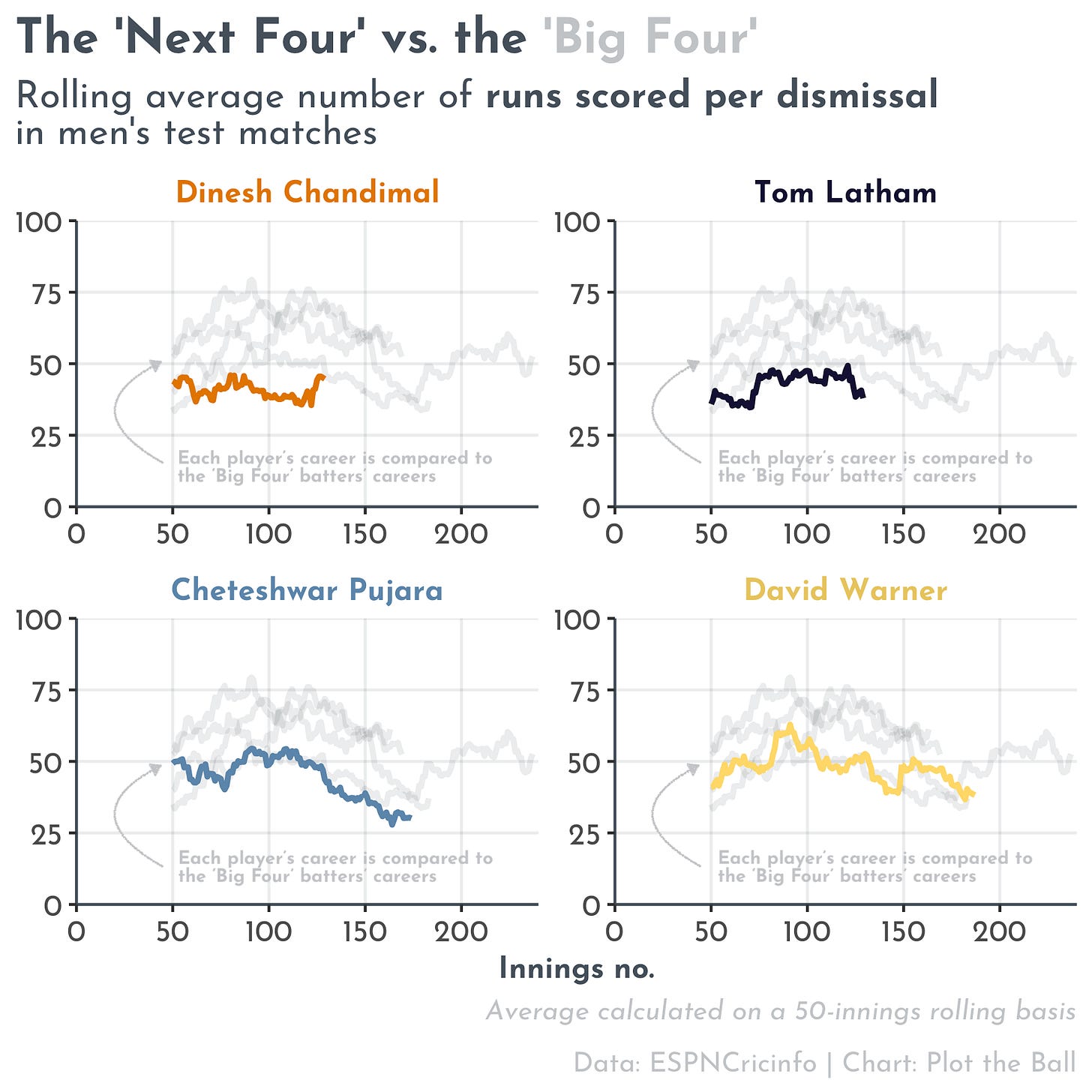

The other four active players in that category introduced above — 5,000 runs since a debut in 2010 or later, at an average of 40 or better — are (in alphabetical order): Dinesh Chandimal, Tom Latham, Cheteshwar Pujara and David Warner.

Each of the four have spent their test careers operating in the foothills of the terrain occupied by Kohli, Root, Smith and Williamson — and there has often been considerable overlap at comparable stages of their respective careers.

This is particularly true in the case of Pujara and Warner, whose exemplary home records are overshadowed by markedly poorer returns away from their respective home countries6.

We shouldn’t underestimate the quietly impressive careers that Chandimal and Latham have put together too. While their peaks aren’t as high, they have both reached marks in overseas tests that neither Pujara nor Warner can match7.

Their steady consistency over time is also notable. In elite sport, it’s often the case that you have to continually evolve your skills just for your performance levels to stay in one place — and how difficult it is to do this is clear in the volatility of even generationally great batters like Root and Kohli.

In this context, Steve Smith and Kane Williamson — whose test careers to date have been defined by their sustained mastery — are even more impressive.

You can find the code for this piece on GitHub here

With the exception of ice hockey, which I’m planning to write about again soon.

Karthik Krishnaswamy of ESPNCricinfo contextualised this innings well; you should read that piece, and every other word of his coverage of the Border-Gavaskar Trophy series for the site.

Were Pakistan’s Azhar Ali — who retired at the end of last year — still playing, it would have been nine.

A metric along the lines of the ‘runs vs. expectation’ concept I’ve previously outlined for T20 could also be applied to four- and five-day cricket to incorporate some of this context, and this is something I’m planning on looking into in future.

Using 50-innings rolling averages here gives me considerable confidence that the variation in performance isn’t just a result of randomness.