🏉 Men's international rugby union changed gradually — then suddenly

Heading south

Welcome to the 15th edition of Plot the Ball for 2023.

If you missed the previous edition, you can read it here:

The Rugby Championship — the premier international men’s competition in the Southern Hemisphere — starts at the weekend. As we did in advance of the Six Nations, let’s dive deeper into some results data in order to set the scene.

Substack has recently launched a subscriber referral scheme, which enables writers to offer additional benefits to readers who spread the word about their favourite publications.

If you enjoy this newsletter, please consider inviting a friend to read it too. By following these instructions, you will start to earn a number of additional rewards whenever they subscribe!

Men's international rugby union changed gradually — then suddenly

The beauty of sport is almost always in the details.

But spend all your time observing up close and — somewhat antithetically — you put yourself at risk of missing some of the important things.

Occasionally, at that level of remove, events can transpire which feel shocking.

Ireland going into this year’s Rugby World Cup as the best team in the world is something pretty unusual in the history of men’s international rugby union, for instance.

But step back a bit and you can see that it’s representative of a much deeper shift that’s happened in the sport.

Australia, New Zealand and South Africa have — until recently — existed as a (fairly) united bloc in the rugby world.

And they have tended to dominate the flagship international tournament in the men’s game: between them, they have won eight World Cups out of nine, been the runner-up in a further three and finished third in another six1.

But they’ve also had their player bases constantly eroded away by European club teams2 offering more generous financial packages and often enviable lifestyles.

The headline numbers at World Cups might make you think that there’s simply a never-ending flow of talent coming up through the ranks behind the players who depart to fill the void.

But knockout competitions are a notoriously poor gauge of actual team strength; a single result can hide a multitude of underlying issues.

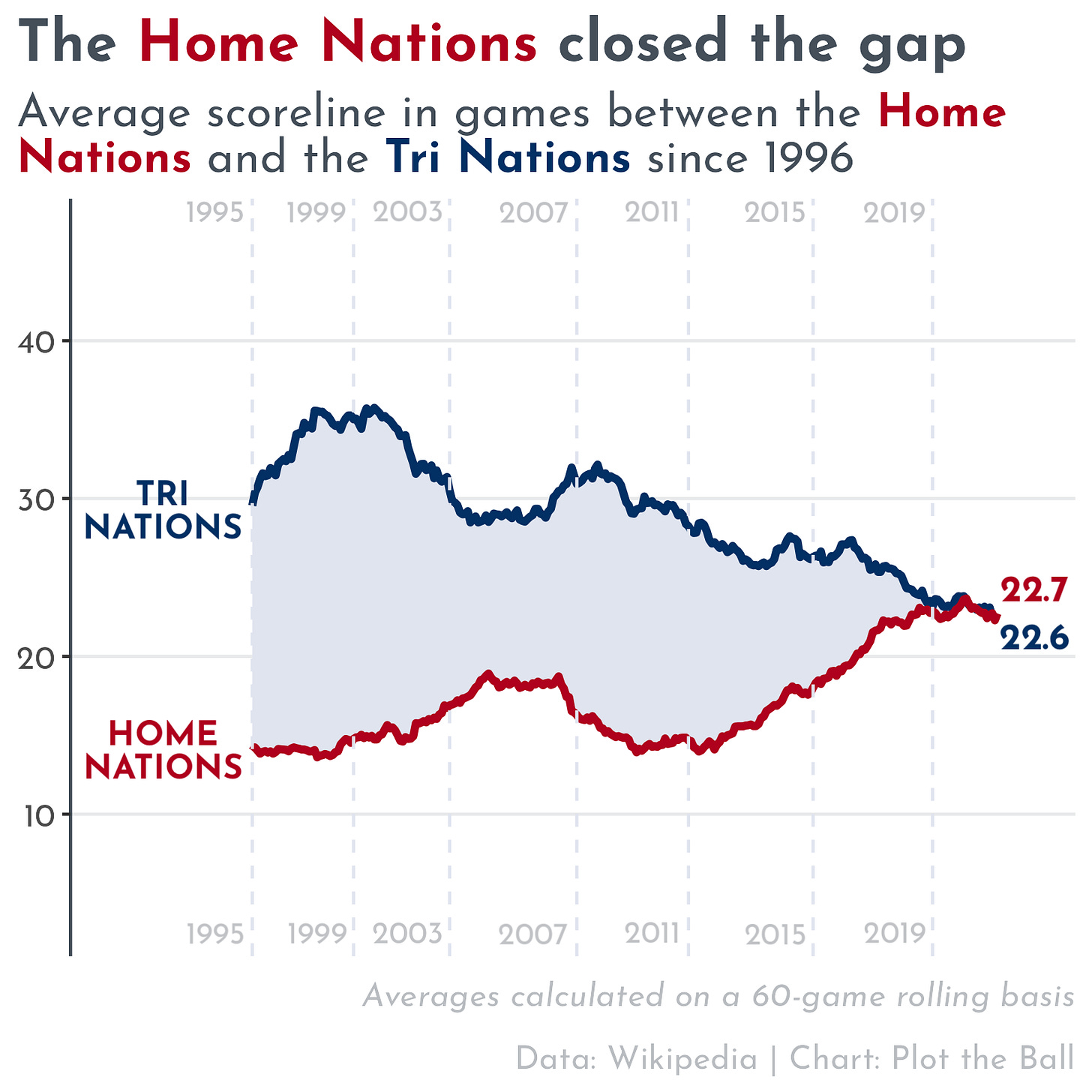

And the picture really has shifted radically over the professional era. The Tri Nations trio of Australia, New Zealand and South Africa were hugely dominant at the time rugby turned professional in the mid-1990s — but their historical advantage over their English-speaking competitors3 in the Northern Hemisphere has now been completely eroded.

Over the last 60 games that Australia, New Zealand and South Africa have played against England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland, the European nations have come out just on top in the aggregate: the average score during this stretch was 22.7 points to 22.6.

Over the first 60 games of the professional era, for reference, the average scoreline was 34.0 to 14.9 in favour of the Southern Hemisphere teams.

This is the sort of shift that is imperceptible for a long time to even the most skilled observer, and only becomes properly clear when you look at the data like this over the long-term.

Going into the World Cup — and the Rugby Championship, which starts this weekend and in which the Tri Nations countries compete along with Argentina — this is how discussions of specific teams and potentially historic outcomes need to be framed4.

Over the next few months, by all means, enjoy the microscopic moments which can make rugby a beautiful sport to watch — a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it break from New Zealand’s Will Jordan on one side of the ball, for example, or the exquisite violence of a Garry Ringrose tackle on the other.

But make sure you also step back and consider these longer-term trends if you want to comprehend more fully what’s going on in the international game.

One of rugby’s traditional Southern Hemisphere powers may well end up winning the World Cup again — and the next few weeks will provide an indication of who is shaping up well in their quest to do so.5

But, even if they do, don’t be deceived: we’re living in a different world to that of the 1990s and 2000s.

Men’s International rugby is not the same sport it used to be.

You can find the code for this piece on GitHub here

Brian Fitzpatrick — who I’ve worked with previously on some rugby-related projects — is currently hiring a rugby analyst for his company, BF Sports Analysis. If you are able to work in Ireland and interested in finding out more, you can read about the role here.

Australia have two wins, two second-place finishes and one third place finish; New Zealand have three wins, one second-place finish and three third-place finishes; South Africa have three wins and two second-place finishes.

Of the 92 players named in matchday squads for the finals of the two major European club competitions — the Champions Cup and the Challenge Cup — 6 learned their rugby in Australia, 7 did so in New Zealand and 8 did so in South Africa: 21 in total, or almost a quarter of the players who featured.

I’ve excluded France here as they have historically been a pretty volatile team; I’ve excluded Italy as — despite the odd result here and there — they remain miles behind the other European sides.

As an aside, it’s also worth considering what this trend line means for British & Irish Lions tours past and future. Equivalent performances in terms of points margin in different stretches of the professional era should be weighted vastly differently, and — if things continue along the current trajectory — they may soon begin to lack real jeopardy.

Over their last 30 games against Tier 1 opponents, Australia’s have scored 23.5 points on average and conceded 26.4; New Zealand have scored 32.7 and conceded 19.7; South Africa have scored 27.8 and conceded 18.8.