🏈 Are elite NFL quarterbacks getting more explosive?

Dual threat

Welcome to the ninth edition of Plot the Ball — a newsletter where I offer data-driven answers to interesting questions I have about the world of sport.

This month — after getting up to speed with the first half of the 2022 NFL season — I’ve been thinking about quarterback play in American football, and wondering how it has developed over the last couple of decades.

I have a free month of paid subscriber benefits (worth £5) to Grace on Football to give away to two of my own subscribers.

If you’d like to receive one of these gifts, reply to this email or comment below.

Are elite NFL quarterbacks getting more explosive?

One of the great privileges so far of my life as a sports fan was getting the opportunity to watch Tom Brady — not far from his (arguable) peak — dissecting an NFL defence at Gillette Stadium on a freezing late-December day in 2009.

The box score from that game — a comfortable 35-7 win for Brady’s New England Patriots over the Jacksonville Jaguars — tells me now that the star quarterback was at his efficient best: he completed 23 of his 26 attempted passes to teammates, including four for touchdowns.

The memory of the day that I’m stuck with, however, is not one particular scoring pass or another.

Rather, it’s the serene awareness that Brady projected every time he stood in the pocket, shuffling back and forth away from defensive pressure to find the space necessary to release the ball towards its intended target downfield.

Trying to play quarterback in the NFL is possibly the purest distillation of the fundamental challenges of pattern recognition and skill execution that professional sport presents — and, for many years, it felt like the cocoon of control that Brady exists within on the field represented the model answer for this test.

To glance at most NFL highlights packages in 2022, however, is to garner the impression that the textbook has been torn up.

Watching brash young gunslingers like Patrick Mahomes, Lamar Jackson and Josh Allen scrambling around in the backfield extending plays (or running into space themselves when defences offer it to them) is an experience fundamentally different to — and much more dynamic than — watching Brady operate on a sheltered island behind his offensive line.

But such an impression — based a small number of salient examples — can of course be misleading. To assess just how accurate it is, we need more data points.

Looking at the crop of athletes who have entered the league since the beginning of this century, let’s ask: to what extent has more confrontational and explosive quarterback play truly become the norm across the NFL?

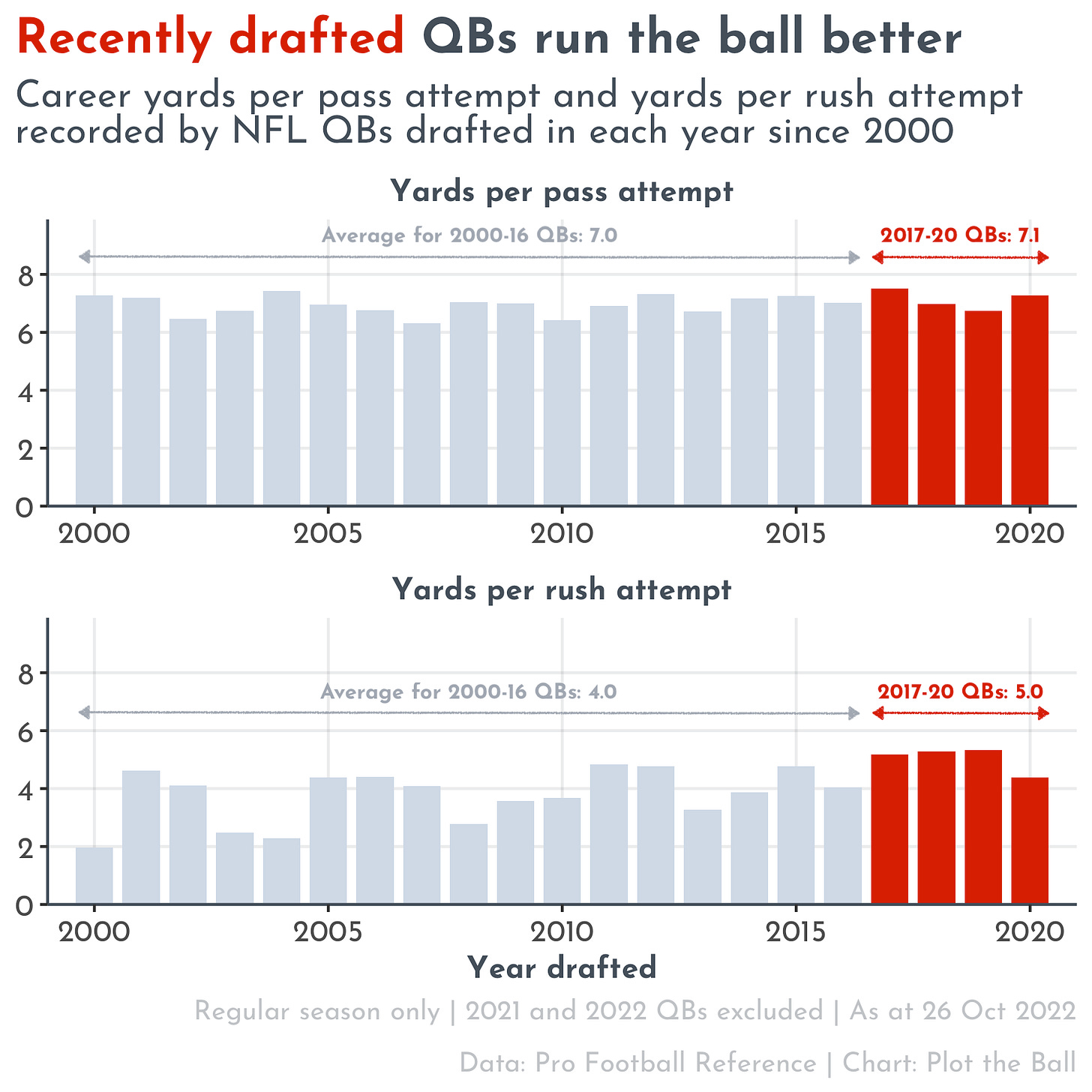

While they are far from perfect for holistically assessing player performance, passing yards per attempt and rushing yards per attempt are useful metrics for what we’re trying to get at here.

Put simply, they approximate the rate at which players move the ball downfield when they attempt to pass the ball to a teammate or run the ball themselves — reasonable stand-ins for ‘dynamic’ or ‘explosive’ performance in each of the two main facets of a quarterback’s game.

Grouping quarterbacks together into draft classes1 and looking at their combined career performance by these two metrics presents quite a clear picture: while the rate at which cohorts have moved the ball downfield with passing plays is fairly consistent across the last couple of decades, more recent classes of drafted quarterbacks have brought more explosive running games with them into the league.

And — while these cohort averages are pulled upwards by elite rushers like Jackson (6.1 yards per rush in his career), Kyler Murray (5.7) and Allen (5.5)2 — even the least dynamic quarterbacks are running the ball much more effectively that they used to.

As the chart below shows, no quarterback drafted since 20173 has averaged less than 2.9 yards per rush in their career to date — while 34 players at the position drafted between 2000 and 2016 have done so.

Where Brady (1.7 yards per rush) and the other leading quarterbacks of his vintage were steadfastly one-dimensional4, even the more traditional passers in today’s game offer more variety.

Players like the Cincinnati Bengals’ Joe Burrow and the Los Angeles Chargers’ Justin Herbert pass the ball much more frequently than they run it, averaging around 11 passing attempts for every rushing attempt5 — compared to ratios of around 5:1 for Allen and Murray, and 2:1 for Jackson.

But they are much more effective than Brady et al. when they do keep the ball themselves: Burrow averages 3.6 yards per rushing attempt for his career to date, and Herbert averages 4.2.

It’s clear, then, that the answers offered by NFL quarterbacks to the questions they face every week really are evolving.

Still a regular starter in the league at the age of 45, it is undoubtedly impressive that Brady has stuck around long enough to see this revolution take place — he just might not be enjoying watching it as much as the rest of us.

Further reading

Dane Beavers (and others) of ESPN on the three distinct phases of Tom Brady’s career

Bill Barnwell of ESPN on quarterbacks (including Joe Burrow, Lamar Jackson and Patrick Mahomes) who broke out in their second professional season

Steven Ruiz of The Ringer on Justin Herbert’s game (ahead of the 2022 season)

Kevin Clark of The Ringer on Mahomes’ game (ahead of the 2021 season), Mahomes’ game (ahead of the 2022 season), Josh Allen’s game (ahead of the 2021 season), Josh Allen’s game (ahead of the 2022 season) and Burrow’s game (ahead of the 2022 season)

Technical notes

You can find the code for this piece on GitHub here

In last month’s newsletter, I talked about removing solid reference lines for scatter plot axes with non-zero baselines. Both axes in the second chart above fell into this category — rather than just one, as in last week’s scatter plot — and so I decided that I needed to make the purpose of the axis labels more explicit by adding a horizontal and vertical arrow next to the x- and y-label respectively. I think this maintains the clean look, while ensuring that the floating labels inside the body of the chart are less likely to be misinterpreted.

Again continuing on from last month, I wanted to focus on using the annotation layer to reinforce the key message of each visualisation. For simplicity’s sake — and inspired by Tom Worville’s argument in its favour when he appeared on the Explore Explain podcast — I have just been using Preview (the basic image-editing app native to MacOS) to add annotations to the charts which appear in this newsletter, and am currently a fan of its double-ended arrow for referring to specific ranges on a given axis (and to impart associated colour encodings).

I also wanted to experiment with concerted repetition of key visual elements to reinforce this edition’s message — hence the colour encodings remaining consistent across both of the charts above, and the first chart’s title simply being repeated verbatim at the top of the second. It’s not particularly subtle, but hopefully has the desired effect!

I’m a big advocate for the approach of Lisa Charlotte Muth (of Datawrapper) to using the colour grey — “the most important color in data visualization” — in charts, and wanted to use it to encode the “less important data” here. Even though I added a slight blue tint to the shade I employed in both of the charts above, when it came to using it for annotations there wasn’t sufficient contrast with the white background for them to be sufficiently readable. I therefore dropped the brightness of the colour used in the text annotations, while trying not to stray too far from the colour used for the data and losing the necessary association.

Next month will be the 10th and final edition of Plot the Ball for 2022. After a short break, the newsletter will be returning at the start of next year in a revised format.

For the final edition of the year, I’ll be returning to the sport which featured in the first edition, and — to coincide with the end of this year’s Big Bash — looking at whether there’s a new MVP in Australian women’s cricket.

Putting Brady, for instance, in a cohort of 12 players who all entered the league via the 2000 NFL Draft.

All of the 12 quarterbacks who have entered the league this century and averaged more than 7 yards per pass attempt and 5 yards per rush were drafted in 2011 or later, and six have been drafted since 2017.

Excluding those with fewer than 500 combined career passing and rushing attempts.

Seven of the eight quarterbacks who have entered the league this century and averaged more than 7 yards per attempt and fewer than 2 yards per rush were drafted in 2004 or earlier; this group includes Brady, Drew Brees, Eli Manning, Phillip Rivers and Matt Schaub.

For comparison, Brady is at a ratio of 17 passing attempts per rushing attempt for his career.