⚽️ Are there any good goalies?

My Week in Sport(s): keepers in men's club football, hockey in the USA and more on Phoebe Litchfield

Welcome to My Week in Sport(s) — a new regular newsletter from Plot the Ball.

In this edition:

⚽️ Assessing goalkeepers in men’s football

🏒 The NHL’s expanding pool of talent

🏏 Phoebe Litchfield’s expanding range

⚽️ Are there any good goalies?

Whether or not we choose to acknowledge it1, there is uncertainty inherent in every sporting action and contest.

We can’t just shrug in every instance and apply the same margin of uncertainty to all of our judgements, though.

The degree of certainty we should have in a given case is contingent: both on the nature of the sport we’re looking at, and on the specific action we’re contemplating within that sport.

Michael Lopez’s famous study of the postseason formats of the four major North American men’s leagues is an excellent illustration of the fact that the likelihood of the ‘better’ of two competing teams winning a given game can vary considerably from sport to sport.

And a recent series of posts by David Sumpter — co-founder of analytics company Twelve Football — demonstrated the fact that, within a single sport, there can be considerably more variability in some skills than others.

Sumpter shows that we can be pretty sure — barring any major changes in circumstances — that a top striker like Erling Haaland will produce similar underlying outputs season after season2: a player’s individual expected goals per 90 minutes is a “highly repeatable” measure.

Such repeatability allows us to make confident statements about this specific player’s skill: Haaland, it is clear, is one of the best in the world at generating high-value scoring opportunities for his football team.

At the other end of the pitch, though, things are nowhere near as straightforward. Analysing the goalkeeper position is a fraught exercise — for a number of reasons.

To start with, keepers are at the mercy of something almost entirely outside their own — and even their teammates’ — control: how well their opponents execute their shots on goal.

It’s possible to try and adjust for this factor in analysis of their performances — but, as we will see, even the best public measures of isolated goalkeeping skill are much further from perfect than something like xG is for chance creation.

Let’s illustrate this by looking at the performances of goalies in the top five men’s leagues since the 2017-18 season.

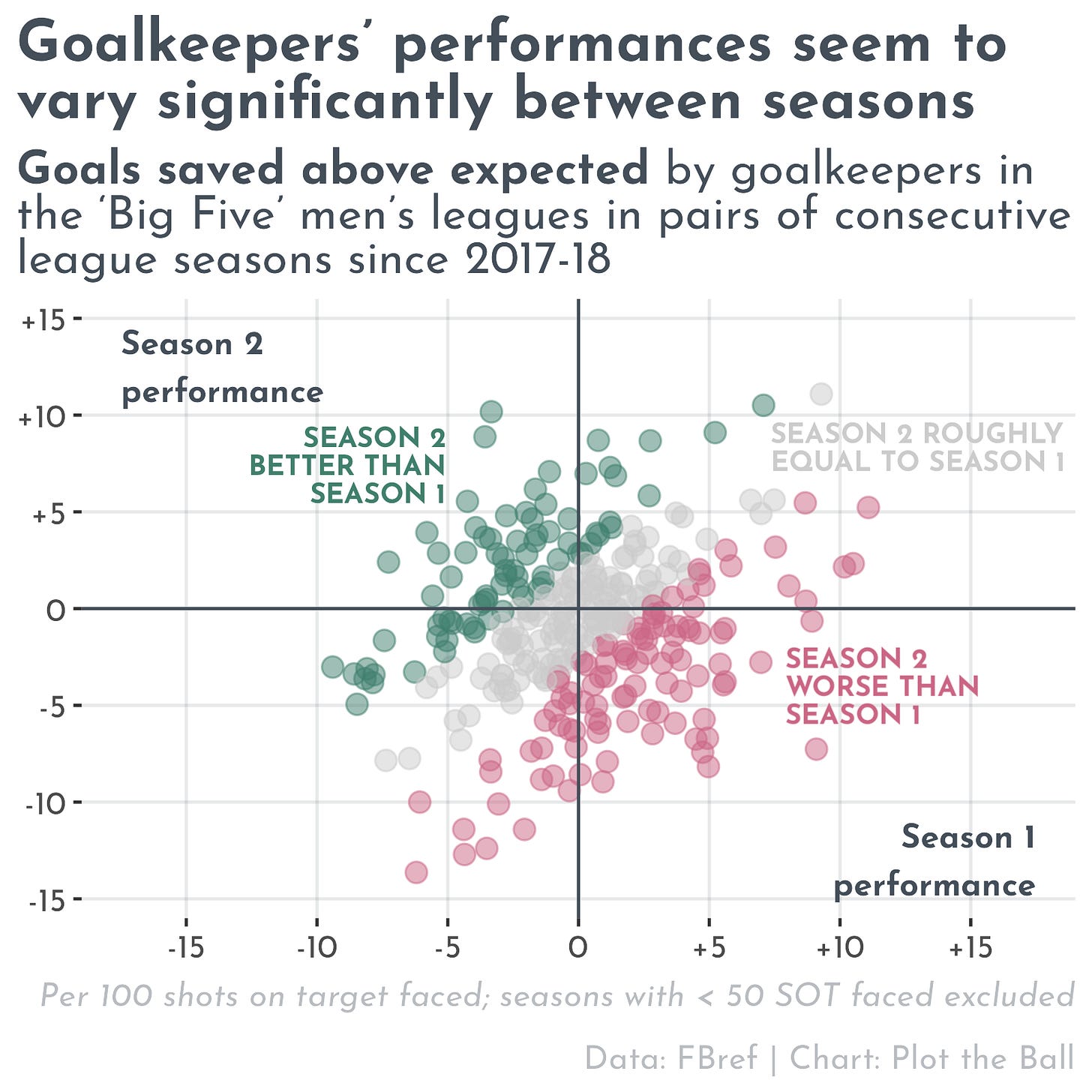

On the chart below, each dot represents a pair of consecutive seasons played by one individual goalkeeper for one club team3.

Their performance in the first season of this pair is plotted on the horizontal axis, and their performance in the second season on the vertical axis.

‘Performance’, in this context, is measured by looking at how many goals they conceded relative to expectation for every 100 shots on target they faced in net.

This expectation is based on Opta’s ‘post-shot expected goals’ metric: a model which assigns to each shot a probability that it will turn into a goal, based on the part of the goal it’s aimed towards.

There are certainly goalkeepers who tend to produce good performances year after year by this measure: Atlético Madrid’s Jan Oblak is one of them.

For every 100 shots on target he faced during the 2017-18 season, Oblak saved 9 goals above expected. The Slovenian international then bettered that mark in 2018-19, saving Atleti 11 goals above expected.

But even Oblak is not immune to down years. Remarkably, between 2020-21 and 2021-22 his underlying performance swung from 9 goals saved above expected per 100 shots on target in one year to 7 goals conceded above expected the next.

And these sorts of major swings are not at all uncommon.

Looking at all of these pairs of seasons by goalies and categorising them based on how close the second year’s performance was to the first, we can see how uncertain our grasp on goalkeeping skill is.

Across the hundreds of pairs of player-seasons which qualify for this analysis, there is some correlation between years — but nowhere near as much as there is when outfield players’ ability to create scoring chances is analysed in the same way4.

All in all, only in 41% of cases was a keeper’s season-two performance within 2.5 goals — in either direction — of season one.

A slightly smaller proportion produced much worse numbers in season two than season one, and only in 26% of season pairs did the goalie markedly improve year on year.

Part of the story here is the variability in outcomes of difficult athletic skills — both kicking a football, and attempting to catch or parry a football — we’d expect to see over what are still relatively small samples of actions5.

But the information we have is also far from perfect. It’s great to have access to public PSxG models6 like Opta’s — but there are still a number of missing pieces within them.

In an excellent piece published at American Soccer Analysis in August, Kieran Doyle and Mike Imburgio highlighted one of these major issues.

The goalkeeper’s own positioning should be a crucial aspect of how we judge the probability of a shot at a given part of the goal going in — but this doesn’t seem to be adjusted for in the data tracked by Opta.

Put these factors — expected variability, and imperfect public information — together, and you have a really uncertain picture.

In short, even our best method of assessing a goalkeeper’s underlying performance in a given season will be unable to pinpoint their ‘true’ skill level at that point in time with any real precision.

Thanks to advanced data provided by the likes of Opta, if someone asks you to name the best ten strikers in men’s football, you can probably answer pretty confidently.

If you’re asked the same question about goalies, though, all you can really do after listing one or two names — for the time being, at least — is shrug.

🏒 Run the Numbers

Something I’m planning to publish in the near future is an analysis of the origins of players who have made recent NHL All-Star teams — in the same way I investigated All-NBA selections in men’s basketball last year.

For the time being, though, studying John Barr’s recent piece for Sound of Hockey on bottom-up demographic trends in the NHL has been fascinating.

Since the early 1980s, the share of Canadian players in men’s ice hockey’s strongest league has been steadily declining — from over 80% at that point in time to around 40% this season.

It’s the USA — where 25 of the league’s 32 teams are based — which has grown substantially while the contributions of its northern neighbour have shrunk. And one chart in particular — titled ‘The changing landscape of USA NHL players’ — caught my eye.

As John notes in the piece, it’s pretty clear that the league’s strategy of expanding into areas where hockey isn’t traditionally played has paid off in one important way: a corresponding expansion in the size of the sport’s pool of potential talent7.

🏏 Watch the Games

In what I’m counting as the first official instance of the Plot the Ball curse, young Australian batter Phoebe Litchfield went into one of the worst slumps8 of her WBBL career almost immediately after I wrote about her back in October.

In Australia’s recent T20 International series win over India, however, she got back on track: facing 57 deliveries across three innings, she scored 22 runs above expectation.

I wrote about her ability to access the off side of the field in my previous piece, but — after the first game — analyst Jeet Vachharajani9 noted her ability to hit for power through the leg side too.

In the 13th over of the match, Litchfield pulled consecutive deliveries over the ropes for six. She shuffles down the pitch to meet the first ball with momentum; ahead of the second, she correctly guesses how the bowler will respond, and moves deep in the crease to execute the shot from a strong base. Watching the boundaries back to back is hypnotic.

You can watch a clip of this sequence here.

The next edition of My Week in Sport(s) will be published on Saturday January 20th.

Almost a year ago, I texted a friend to complain about Jonathan Liew — one of my favourite sportswriters — stating the following: “Arsenal will be champions. It’s about time someone committed this to print.” You’re probably aware how that turned out.

Haaland produced 0.75 non-penalty expected goals per 90 minutes in last season’s Premier League; so far this season, he has produced 0.81 per 90.

I think it’s cleaner to exclude pairs of seasons where players represent two different clubs from this analysis — although work by Eduin Latimer for Analytics FC has found (for a related but slightly different metric to the one we’ll go on to look at) that “the difference between year-on-year volatility for stayers and movers is small (and not statistically significant)”.

To check this, I ran a quick analysis of the non-penalty expected goals generated by outfield players per 90 minutes in the ‘Big Five’ leagues over the same period (applying similar criteria and thresholds). The coefficient of correlation between NPxG in season one and NPxG in season two was around 3x as high as it was between seasons for goals saved above expected.

234 was the highest number of shots on target faced by any goalkeeper in a single season over this period — by Sam Johnstone of West Brom in the Premier League in 2020-21.

We got a peek behind the curtain at StatsBomb’s private goalkeeping model recently, when Ted Knutson shared a snippet of their Premier League data on X; its ranking of Premier League goalkeepers this season differs considerably to Opta’s.

The US men’s U20 team won gold in the 2024 World Junior Championships earlier this month. Of the 25 players on their roster for the tournament, four have places in Florida listed as their hometown, while Arizona and California also provided players.

Only four of her 11 innings subsequent to publication had a positive impact relative to expectation, by my updated calculations; she used up 67 deliveries in her seven net-negative innings — an average of 9.6 balls per dismissal.

You’ll need to request to follow Jeet’s account on X — which is private — to see the clip under discussion; alternatively, you can watch the second and third shots in this video.