Welcome to the second edition of Plot the Ball — a newsletter where I offer data-driven answers to interesting questions I have about the world of sport.

This month — as action in the men’s Champions League has resumed — I’ve been thinking about the unlikely path to contention taken by Ajax, and wondering whether it signals a change in approach at one of European football’s most storied clubs.

Has 'the Ajax model' changed?

Few professional sports teams have as distinctive an identity as AFC Ajax — and it’s no surprise that club legend and current CEO Edwin van der Sar (speaking in 2017) was able to articulate it pretty clearly.

A trio of European Cup trophies between 1971 and 1973 playing an almost inimitable brand of football — after which the team’s star, Johan Cruijff, departed for Barcelona at the age of only 26 — would likely have been enough on their own for the club’s legacy to endure for decades.

However, another win in the competition now known as the Champions League in May 1995 undoubtedly cemented it.

Louis van Gaal’s construction of a precociously talented squad (their 1994-95 side was just 23.9 years old on average, while their opponents had an average age of 26.5) and institution of a similarly daring (if slightly more rigid) style of play brought a fourth major European title home to Amsterdam — and almost brought a fifth home in 1995-96.

But when that team disbanded, a barren period followed.

In the two decades after van Gaal left Ajax in the summer of 1997, the club managed only a single trip beyond the last 16 of the Champions League — losing to eventual winner, AC Milan, in the 2002-03 quarter-finals.

Then, in the 2018-19 season — with van der Sar and Marc Overmars, teammates in 1995, coordinating things off the field — the club threatened to do it all over again.

(Overmars — who had been appointed director of football in 2012 — recently left the club in disgrace before a Dutch newspaper could reveal how he had repeatedly abused his power over female employees.)

Led by new manager Erik ten Hag — a branch of Pep Guardiola’s coaching tree — Ajax were a whisker away from reaching another Champions League final with a team that represented a modernisation of the tactics with which the club were once synonymous.

And, like with van Gaal’s squads, youth was to the forefront: their European campaign saw them field a team with an average age of 24.3 years, compared to their opponents’ average of 27.1.

Things didn’t fall completely into place for that side, but in 2021-22 they have returned to the top table with a real chance of going one better.

After drawing the away leg of their round-of-16 clash with Benfica on Wednesday, FiveThirtyEight’s Club Soccer Predictions give Ajax a 32% chance of reaching this year’s final — a mark that only superclubs Liverpool and Man City can better.

As some observers have noted, however, there’s a different feel to this year’s team.

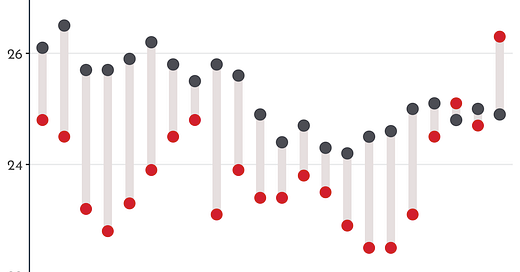

What has changed becomes obvious when you look at the playing time data collected by FBref on each of Ajax’s domestic league campaigns since 2000.

After years of fielding consistently younger teams than the Dutch clubs they faced in the Eredivisie, in 2021-22 they have selected players markedly older than their opponents’.

While other teams have consistently remained around the 25-year mark, Ajax’s average age (weighted by minutes played) in domestic fixtures has jumped by 24.7 last season to 26.3 so far this year.

(The ban of André Onana — and his replacement in goal by 38-year-old Remko Pasveer — explains a substantial proportion of this increase. However, even if Onana had played all of Pasveer’s minutes so far, this would still be the oldest Ajax team in FBref’s Eredivisie database — and they would still be around half a year older than their opponents.)

Comparing the prior playing experience of the key members of their 2021-22 Champions League squad to that of the 2018-19 squad provides additional context.

Looking at data up to the end of the season prior to each campaign (i.e. 2017-18 and 2020-21), the ’18-19 crop had spent more of their careers at Ajax than the ’21-22 squad. Conversely, they had notched up much less playing time at other clubs — in particular, many fewer minutes at clubs in Europe’s elite ‘Big 5’ leagues.

The process that Overmars had begun in the summer of 2018 by bringing veterans Daley Blind and Dušan Tadić back to the Netherlands (from Premier League clubs Man Utd and Southampton respectively) has continued in recent seasons.

To supplement the young talent coming through De Toekomst, Ajax have since brought in other peak-age players once deemed good enough for those elite leagues: former captain Davy Klaassen returned to the club from the Bundesliga, Ivorian international Sébastien Haller was signed from West Ham and Steven Berghuis — who had a brief stint in England in 2015-16 — was signed from club rivals Feyenoord at the age of 29.

(Blind, Tadić, Berghuis and Haller all started Wednesday’s game in Lisbon, while Klaassen came off the bench to play 20 minutes.)

Whether or not this is a sustainable long-term strategy for the club, however, is open to question.

2018-19 marked the start of Ajax’s commitment to running a significantly higher annual wage bill, as data collated by football finance expert The Swiss Ramble shows.

Continuing to support this level of salary costs in each of the following seasons appears to have only really been possible because of the windfall they received from progressing as far as they did in that season’s Champions League — and by generating large profits from the sale of the young stars that got them there.

Another deep European run would bring with it more valuable broadcasting revenue from UEFA — but the more experienced make-up of this year’s squad in contrast to ’18-19’s means that fewer lucrative player sales are likely.

This is especially true in a footballing world that has struggled — outside the Premier League, at least — to cope with the shock that Covid-19 represented to its financial system.

While it reduces the likelihood of expensive outward transfers, this is a factor that could work in Ajax’s favour in another way. Having worn the impact of the pandemic better than other members of the European elite, there’s a chance it could be better placed to pick off more talent from traditionally stronger leagues in continental Europe than it was a couple of years ago.

(Michael Caley and Mike Goodman discussed a version of this dynamic on a subscriber-only episode of The Double Pivot Podcast in December.)

Ultimately, though, pursuing this approach wholeheartedly would be a taking a risk based on factors outside of their own control. The safer option for the club would be to fall back on their traditional strength of talent development.

After all, it’s a story that they — and we — have seen work before. As van der Sar said: “That is what people like about Ajax.”

Further reading

Simon Hughes of The Athletic on director of football Marc Overmars’ recent resignation

Leander Schaerlaeckens of Yahoo! Sports on some of the context for the club’s diminished status in the 21st century and the same topic again during their 2018-19 Champions League run

Thomas Markhorst of The Analyst on the on-field hallmarks of this year’s side

Ryan O’Hanlon on the statistical profile of this year’s side (for No Grass in the Clouds), 2018-19 star Hakim Ziyech (for FiveThirtyEight) and 2018-19 star Frenkie de Jong (for The Ringer)

Tom Hamilton of ESPN on 2018-19 star Matthijs de Ligt and the system that moulded (and eventually sold) him

Jacob Steinberg of The Guardian on that system

Rory Smith of The New York Times on that system

Michael Sokolove of The New York Times Magazine on that system

Technical notes

You can find the code for this piece on GitHub here

After attending a workshop on the topic run by Lisa Charlotte Muth (and hosted by Graphic Hunters), I’ve been thinking a lot about colour choices this month. The more I read and learn about this area, the more I realise I don’t know — but I’ve tried to put a couple of small new things into practice in the charts above. After locating Ajax’s specific shade of red and using that as the primary colour for the key data point in the first chart, I experimented with altering its saturation and brightness (while maintaining the same hue) to produce a pair of complementary shades for the second chart. (The grey line linking data points in the first chart also has a little bit of a tint to Ajax red too.) I’m still not completely happy with this — the contrast between the lighter red in the second chart and the white background probably isn’t good enough — but it’s something I’ve resigned myself to having to chip away at gradually over time. (Lisa’s writing on this topic for the Datawrapper blog is well worth your time — and her forthcoming book is sure to be excellent too.)

To create the dumbbell plot, I relied heavily on the BBC Visual and Data Journalism team’s ‘cookbook for R graphics’ — which is available to read online here — and used the

ggaltpackage at their direction. One change I did make to the BBC’s example was to flip the axes, with the story of change over time appearing a bit more clearly (at least to my eye) as the dumbbells move from left to right.While it was straightforward to identify a chart type that fit the story I wanted to tell with the Eredivisie playing time data, the stacked bar chart I ended up using for the playing history of the two Champions League squads was the result of a longer process. I was basically trying to expand on what the average age of the team’s 2021-22 squad really represented in practice, and after discarding a couple of overly complicated attempts at scatter plots settled on three pairs of bars. There’s a lot of ink on the plot, but after feedback on an earlier draft concluded that splitting the bars up, making the facet labels more detailed and annotating the second pair (done hastily in Preview, not R) was necessary to convey the narrative. (Being able to top and tail it with explanatory text always helps too.)

Finally, it’s worth mentioning that the

worldfootballRpackage made obtaining the data from FBref that I needed for these analyses a breeze. (It also has functions to pull data from Transfermarkt, Understat and fotmob.)

Next month — to coincide with what may yet be the start of the 2022 Major League Baseball season — I’ll be looking at whether there’s anything interesting left to say about one of the most remarkable players in the modern era of professional sports.