🎾 How good can the next generation of tennis stars become?

Hotshots

Welcome to the sixth edition of Plot the Ball — a newsletter where I offer data-driven answers to interesting questions I have about the world of sport.

This month — after watching another engaging couple of weeks of action in the English sunshine at Wimbledon — I’ve been thinking about the legends of tennis who are not far from stepping away from the sport for good, and wondering who is most likely to eventually replace them at its pinnacle.

How good can the next generation of tennis stars become?

It is foolish to attempt to predict exactly when any sport will transition into the next stage of its life cycle. It is not too much of a stretch, however, to predict that professional tennis will have moved to a very different place by the end of the current decade.

A number of era-defining players born in the 1980s have won more Grand Slams over the last twenty years than all but a couple of players who went before them — but Father Time, as they say, is undefeated.

Who, then, are the generational talents likely to take over top-level tennis in the 2020s? And how close can they get to the levels of excellence achieved by the players who have dominated the game since the turn of the millennium?

One possible starting point for answering these questions would be an examination of the official world rankings maintained by the ATP and WTA Tours.

But there is a more robust method for estimating player strength in an individual head-to-head sport like tennis than these rankings, which only use the context in which you play a given match — that is, the tournament and the round in which it takes place — as their key input.

Elo models — based on a rating system originally devised by Hungarian-American academic Arpad Elo for chess — set aside this line of thinking, and instead assign an amount of credit to a match’s winner according to the strength of their opponent.

As Jeff Sackmann, the creator of Tennis Abstract’s unofficial Elo rating system for the ATP and WTA Tours, explains:

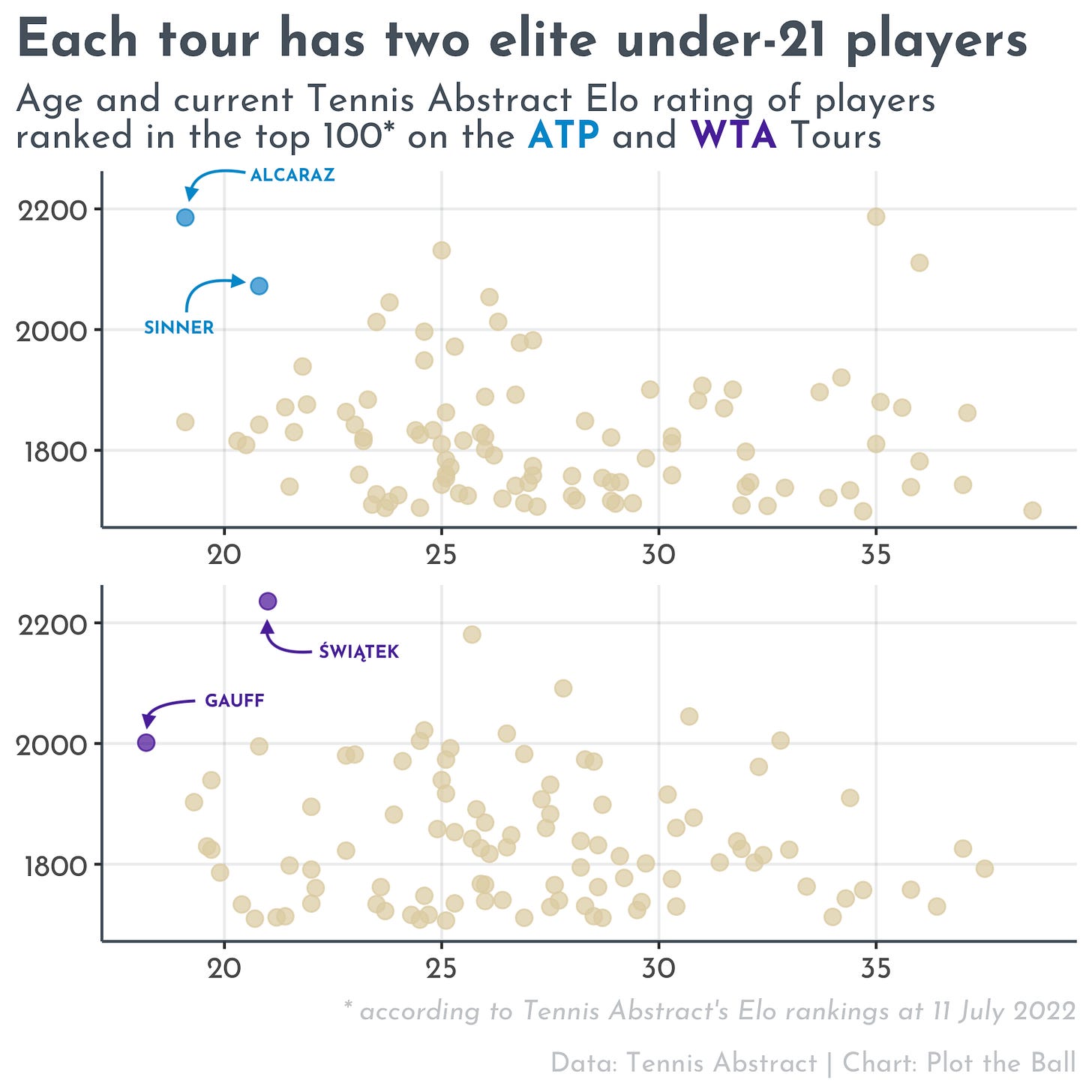

And, according to the Tennis Abstract model, there are two players aged 21 or younger on each tour who are already approaching elite status.

On the men’s circuit, Italy’s Jannik Sinner — who will turn 21 next month — and Spain’s Carlos Alcaraz — who only recently turned 19 — have already passed the 2000-point mark which Sackmann explains is “a good rule of thumb to separate the elites from the rest.”

On the women’s tour, 18-year-old Cori Gauff of the USA and Poland’s Iga Świątek (who recently turned 21) are the pair currently operating at or above this level.

With Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic still among the ATP elite — having won all three Grand Slams so far this year between them, and seven of the nine to have taken place since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic — neither Sinner nor Alcaraz has yet won a major championship.

On the WTA side, however, the changing of the guard may have already happened. Serena Williams — holder of 23 Grand Slam titles — hasn’t prevailed in a major since the 2017 Australian Open, and lost in the first round of the 2022 Wimbledon singles draw having not played a tournament for 12 months.

In Williams’ injury-enforced absence, Świątek — the oldest by a few months of this group of four young guns — has already won two Grand Slams: a maiden French Open title in 2020, and a second earlier this year.

And, according to Tennis Abstract’s rating system, she is likely already closer to her best than Alcaraz and Sinner are to theirs.

According to Sackmann’s database of historic Elo ratings for current top players, WTA stars have tended to reach the peak of their powers earlier than their counterparts on the ATP Tour.

Correction: The chart originally published above was incorrectly labelled (stating that it showed the proportion of players who peaked at each age, with the y-axis labelled accordingly); it has subsequently been corrected and updated.

The chart above shows that the ageing curve is more gradual for this current crop of elite men’s players, and makes clear just how special Alcaraz is to be rated so highly at age 19. (As of 11 July, his Tennis Abstract rating was within touching distance of the 35-year-old Djokovic’s at the top of the men’s rankings.)

But just how good is the Spanish phenom likely to get?

Using Elo to compare players across eras is difficult for a number of reasons, as Sackmann explains on his website, and so a straight comparison of Alcaraz’s raw score according to the model to those of Djokovic et al. at the same age is not a particularly instructive one.

A more fruitful exercise, however, may be to look at the previous era’s best players and examine the trajectories they followed between the point Alcaraz is at now and the implied ‘peak’ of players on the men’s tour (at least, according to the data plotted above) at 26.

Looking specifically at Djokovic, Nadal, Roger Federer and Andy Murray, we can see that they each grew their Tennis Abstract Elo rating by a multiplier of 1-1.2x between their age-19 and age-26 seasons.

Given Alcaraz’s current rating of around 2200, a similar path could put him somewhere in the range of a 2500 rating at age 26 — similar to the level that Djokovic and Williams were each able to reach at their best.

Attempting to foresee exactly how one individual player’s career will pan out is arguably even more foolish than trying to predict the future of an entire sport. But, by 2029 — when Alcaraz should be at or close to his peak as a tennis player — it’s at least possible that we’ll be watching the most dominant player that either professional singles circuit has ever seen.

Further reading

Aishwarya Kumar and D’Arcy Maine of ESPN on Alcaraz’s origin story and the group of teenagers who lit up the 2022 French Open

Jonathan Liew of the New Statesman on the genius of Świątek

Gerald Marzorati of the New Yorker on how the style of tennis played at Wimbledon has changed over the years

The Graphic Detail section of the Economist on how styles of play at the four Grand Slam tournaments have been converging

John Burn-Murdoch of the Financial Times on the enduring prize money gap on the men’s and women’s tours

Ben Marlow and Omar Chaudhuri of Twenty First Group on what the three-set format at Grand Slams means for women’s tennis

Technical notes

You can find the code for this piece on GitHub here

The first chart in this piece is in a simple format I’ve used before for the newsletter: a pair of small-multiple scatter plots. For the second, however, I had a bit more thinking to do. I knew I wanted to show the distribution of the ages at which current players peaked on both tours — and the need for the chart to be comparable across two categories ruled out using a histogram. I also didn’t want to use the

geom_densityfunction to depict a smoothed density estimate; I felt that whatever was gained in an aesthetic sense from a cleaner, simpler plot would be outweighed by the additional complexity of having to explain the mathematical transformation in the copy. Thegeom_freqpolyfunction — which can depict density across a series of buckets with lines rather than bars — would have been a good compromise if I had been able to work out how to fill the area below the line, but I ultimately landed ongeom_areaas my tool of choice (with ‘stat = “bin”’ allowing for the same depiction of density across buckets).Whenever I’ve made decisions on colours in charts for this newsletter so far, I’ve tried to tie my choices to something concrete: shades typically associated with each country’s sports teams in PTB 1, and those present in the relevant team or competition logo in PTB 2, 3, 4 and 5. I wanted to do something similar for this edition, and thought immediately of the official logos of the WTA and ATP. However, because I knew I would be using colour to encode gender in these charts, I didn’t want to fall into the trap of automatically assigning blue to data for men and pink (or a similar shade) for women. Taken together, the violet and light blue of the tours’ respective logos seemed a bit close to conforming to that binary — so I strengthened and darkened the ‘WTA purple’ (in both charts) and washed out the ‘ATP blue’ (in the second chart) to try and downplay this. While this retains the basic association between chart colour and the real-world entity it refers to, I’m on the fence about whether it’s a justified choice even with these adjustments. If you felt instinctively uneasy about the colour choices in the charts above before reading this section, I’d be interested in hearing about it.

Finally, it’s worth checking out Jeff Sackmann’s personal website, blog and GitHub page for more insight into his Tennis Abstract Elo model and his tennis work in general. I’m incredibly grateful to him for making as much data as he does public!

Next month — to coincide with the rescheduled IIHF World Junior Championship — I’ll be looking at whether Canadian men’s ice hockey has another generational talent on its hands.